DEAD BEAR, LIVE INDIANS AND HISTORIC FOOD

Camden Event Spotlights Lenape Culture, Hearth Cooking and a River Shark

By Hoag Levins

| |

May 4, 2003

May 4, 2003

CAMDEN, N.J. -- A dead bear, live Indians and a 200-year-old gourmet recipe were the stars of last Sunday's 18th Century Life Day at the Camden

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| Maryellen Flynn is a retired science teacher who has been researching Lenape Indian culture for 45 years. On the basket to her right is the pelt of a wolf. Larger photo.

| County Historical Society. Lenape culture

Actually, the live Indians were just barely that, pointed out historian and educator Maryellen Flynn, who believes herself to be 1/64th Indian. She learned that fact many years after she began the research that made her a leading authority on the Lenape Indians who once lived in southern New Jersey.

Flynn and her grandson, Timothy Flynn Logue, were among a number of craft and history presenters at the annual event sprawling through the three-building complex and grounds of the Historical Society. Other features included an open-hearth cook, a spinner, a historic gardener, a "Whatzit" colonial artifacts table, quill pen writing, old-time laundry demonstrations, mansion tours, and Finley the River Shark, mascot of Camden's baseball team. 18th Century Life Day is an annual Society event designed to provide educational living history demonstrations of interest to both adults and children.

Indian artifact display

Flynn welcomed a steady stream of visitors to her Indian artifact displays spread out on mats beneath the ancient sycamore tree in the side yard of the 18th-century mansion, Pomona Hall. Flanked by wild animal pelts draped over tall baskets, she was surrounded by an array of authentic Lenape war clubs, stone hoes, necklaces of bear

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| The bear skin is one of 16 different wild animal pelts Flynn uses in her Lenape educational programs. Larger photo.

| claws, hemp fish nets, basketry, and other mysterious implements made of tortoise shell, carved bone, wood, stone and dried sinew. She encouraged everyone to touch the items they were asking questions about.

Flynn was dressed in fringed buckskin trimmed with marginella shells from the New Jersey coast. Around her neck hung a carved stone turtle clan symbol, a small bundle of medicines, and a sheath containing a walnut-handled knife with a flint blade. In one hand, she gently waved the wing of a seagull that was used by the native people as both a fan and a tool of personal interaction.

Seagull wing fan

"The Lenape thought it impolite to point a finger directly at another person," she said, "so they used things like a wing fan to discreetly indicate they wanted your attention."

Her clothes and personal artifacts were those of a 17th-century Lenape

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| A bear-claw necklace (top) and a hemp fishing net with stone weights (bottom) made in the ancient Lenape manner by Maryellen Flynn. Larger photo.

| woman; the garb of her grandson was that of an 18th-century Lenape man.

The Willingboro resident regularly appears at schools and historical functions throughout the region as To-Ki-Pah-Ki-Nao, the Lenape name for "Soft Leaves Woman." A retired teacher, she is quite serious about the accuracy of her presentations and every aspect of Lenape life. For instance, she is a stickler about the correct pronunciation of the widely mispronounced Lenape name: It's "Len-OP-pea," not "LEN-a-pea."

College campfires

She began her unique historical educational career 45 years ago as a student majoring in science education at what was then called Montclair State Teachers College in Sussex County. After vandals stole a large collection of Indian costumes and artifacts from the school's summer camp, Flynn, who knew nothing about Indian culture, was assigned to research appropriate replacements for the native American gear used in the camp's much-cherished campfire rituals.

"I was studying to be a science teacher and I wanted to be 'scientific' and be as accurate as possible for the replacement things," she said.

In effect, that project never ended. After the replacements were acquired and she went on to become a science teacher, she continued to research the history of local Indians as a personal hobby. More than just amassing notes, she began to reconstruct the details

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| Straw mats, baskets, gourds fashioned into containers, bowls hewn from wood, and animal jaw bones were typical of the Lenape's domestic tools. Larger photo.

| of the ancient materials and methods the Lenape used to craft their domestic artifacts.

Knapping flint blades

"I actually began making the stuff," said Flynn, who has created nearly all the Lenape artifacts she now displays. She even learned the ancient art of knapping flint in order to make authentic edged weapons. "It was amazing how razor sharp knapped flint can be -- it was so sharp that I actually had to dull the edges down so they would be safe around kids," she said.

In 1964, during the New Jersey Tercentenary, the state's schools increased their focus on local history and several of her former classmates at Montclair asked Flynn to come into their classrooms to give educational presentations about the Lenape.

"Pretty soon, I was going to schools all over the place and they were giving me honorariums that were enough to allow me to buy animal skins and other items I needed to expand the kind of presentations I could put together," she said.

She nows owns the skins of 16 different wild animals -- including bear, wolf, beaver, racoon and weasel -- that were crucial to the lives and survival of the tribes along the Delaware, the Cooper, the Mullica and other rivers of southern New Jersey.

But, Flynn noted as she patted the pelt of a black bear, the skins have caused her a number of problems in recent years. "The issue of animal skins is a very emotional one today," she said. "I have people ask me why I have to use skins. Well, for one thing, these were all acquired legally a long time ago. Secondly, if you came and watched me when I go into schools you'd see that the skins are what the children touch most. It is the skins that really start to bring the story alive for them."

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| 'Asparagus Forced in French Rolls' was one of the dishes created in the open-hearth kitchen by Hazel Werner. Larger photo.

|

Open-hearth gourmet

Inside Pomona Hall, it was a day of working at a roaring fire for Hazel Werner, a Medford resident who was preparing an 18th-century gourmet treat for the crowds that jammed into the mansion's large, open-hearth kitchen. They watched, fascinated, as she lugged iron pots, scooped up burning piles of coals and slowly assembled the elements of "Asparagus Forced in French Rolls."

Some visitors expressed surprise that such a ponderous and crude-looking collection of iron implements could be used to make a delicate dish that looked as if it could have come from a modern kitchen. "It's heavy work and takes a lot more time, but you can cook really outstanding meals in a kitchen like this if you know what you're doing," Werner said as she placed the finished dish down on a table in front of the fire for all to admire. It consisted of creamed asparagus placed into hollowed-out french rolls browned in butter. Holes were cut in the top and asparagus spears stuck through, as if they were growing.

"This is the kind of food that would have been eaten by the gentry that lived here in Pomona Hall a little over 200 years ago," Werner said. "Life was much more pegged to seasonal crops you could grow nearby then. Asparagus is in season and this is a special treat they would have made at this time of year."

She noted the recipe was from Hanna Glasse, one of the most famous cooks of the 18th century. "She was a genteel lady who found that there was a need for a cook book and ended up creating one of the first," Werner explained. Glasse's "The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy"

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

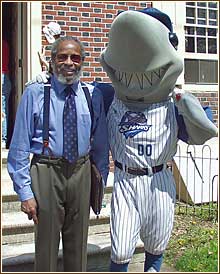

| Posing with Finley the River Shark was Giles R. Wright, Director of the Afro-American History Program at the state Historical Commission in Trenton. He was one of a number of state and local dignitaries who attended the 18th Century Life Day event. Larger photo.

| first appeared in London in 1747 and was a reference book possessed by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson as well as cooks far and wide throughout the colonies.

As she was speaking, an eight-foot-high River Shark cavorted into the room to give her a hug and wave to the crowd.

River Shark history

Curiously, the most historic aspect of the beast was invisible inside the bulky custume: Rutgers student Frank Caruso. The 21-year-old Willingboro resident who has portrayed Finley the River Shark for the last three years is a senior majoring in history and museum studies. He is also working as an intern at the Camden County Historical Society this year.

Pitching in to help at his first Fun Day, Caruso showed up to demontrate the art of being a two-legged, cheerleading fish -- to the great delight of the many adults and children who could not stop taking pictures.

"Man, this is historic said one grinning youngster as he first danced briefly on the sidewalk with the shark and then posed next to the local team mascot as his mother clicked off several images with her digital camera.

All Rights Reserved © 2003, Hoag Levins

HoagL@earthlink.net

About this Web site

|