THE GOLDEN AGE OF CAMDEN COUNTY TUGBOATS

David Boone Captures The History of Delaware River Working Craft

By Hoag Levins

| |

August 10, 2003

August 10, 2003

CAMDEN, N.J. -- To fully appreciate David Boone's history project, you need to know a bit more about those mundane river craft you often glimpse but hardly notice: tugboats.

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| As a teenager, maritime artist and historian David Boone starting riding tugs and sketching Delaware River work boat scenes. Four decades later, he's still at it. Larger photo.

| The fleets of low-slung, bumper-girded vessels exist because of this simple reality: Despite all their power and majesty at sea, oceangoing ships become awkward, helpless hulks when they enter the rivers that lead to their ports of call.

This has always been so. Ships are maximized for operation in open, deep water. They lack the means to control their own ponderous movements in the narrow and shallow confines of rivers.

'Tugging' boats

Even wooden-hulled sailing ships of earlier centuries had to be muscled into and out of their shore berths by row boats whose oarsmen pulled -- or "tugged" -- the mammoth vessels in the correct direction. Eventually, by the mid-19th century, oar-powered "tugging" boats were replaced by larger and tougher-hulled craft powered by steam engines. Such mechanized tugboats have been a crucial part of the daily life and commerce of rivers like the Delaware ever since.

Like wrecking cranes or bulldozers on land, tugboats are pug-ugly waterborne industrial tools designed to exert brute force in often-harrowing circumstances. From afar, their squat, dented silhouettes exude a sense of gritty purpose and battered experience afloat.

Tugboat owners, captains and crewmen are a tight-knit maritime community with a history and heritage stretching back to the Civil War era.

Photo: David Boone Collection

|

| The tug Neptune on duty at the New York Shipbuilding Corporation ways on the Delaware River in 1922. Larger photo.

| And, for the last thirty years, tugboat veteran and maritime artist Boone has been quietly documenting the history of the boats.

Historical Society

In a recent talk at the Camden County Historical Society, the 57-year-old Oaklyn resident showed a selection of slides from an extraordinary archive of more than 15,000 photographs. He displayed sample printouts from his database detailing every tug that operated on the Delaware River from 1885 to 1932. He's now working on the period of 1932 to the present. And he turned the Historical Society's Boyer Auditorium into a one-day gallery show of his intricately-detailed tugboat paintings.

Boone's ultimate goal is to create a book of archival photos, his own paintings and narrative text that captures the in-depth story of a century-and-a-half of Delaware River working boat life.

"There is such a book to be done here," said Boone. "Tugboats were at the center of everything that was happening along the river for as far back as you go in industrial history. It was it's own life out there on the water; there was nothing else like it."

Tugboating and art

Boone's passion for tugboating is grounded in hard experience. In fact, his entire life has been shaped by two intertwined interests: tugboating and art. As a boy growing up in Fairview, he often took a rowboat and sketch pad along Newton Creek to the Delaware,

Painting: David Boone

|

| Two Pennsylvania Raiload steam tugs, the Trenton (built 1916) and the Canton (built 1906), are captured in a 1960 scene at the North American Smelting works at Fieldsboro, N.J. The facility was a major 'bone yard' where old vessels were sent to be scrapped. The decommissioned WWII submarine, Gunnel, sits nearby. Larger photo.

| tying up near the New York Shipbuilding yard. There, he'd draw whatever tugs or other vessels happened to be passing up or down the river that day.

As a young teenager, he began riding tugs as a volunteer worker. "That's how it was done back then," he said. "You'd work for free just to be on the boat and the river. You had to learn everything on your own. Over the years, as you taught yourself the job and proved to them you could do it, you had the chance to get hired for a real job when one became available." But real jobs opened up only rarely in a clannish industry whose well-paid members regularly spent their entire careers on a single boat.

After high school, Boone studied accounting as he continued to roam the river on weekends and holidays. He was a 25-year-old clerk at an auto dealership in 1971 when the call finally came from the Curtis Bay Towing Company that operated the Reedy Point and five other Delaware River tugs. A job was open if he wanted it. Boone leapt into the tug business and never looked back.

Operations Manage

From deck hand and dispatcher he eventually rose through the ranks to become the operations manager of Curtis Bay's Delaware River fleet. And, all the while, he kept sketching, drawing and painting.

Retired from tugboating in 1999, he is now a full-time

Photo: David Boone Collection

|

| The iron-hulled Jupiter is the oldest surviving tugboat still operating on the Delware River. She was built in 1903 and is now part of a growing Penns Landing museum fleet maintained by the Philadelphia Ship Preservation Guild. Larger photo.

| maritime artist, tugboat historian and president of the Tugboat Enthusiasts Society of the Americas. His own enthusiasm is evident in his personal Web site domain: TugBoatPainter.com.

Boone pointed out that from about the 1880s to the 1980s the basic structure of the boats changed surprisingly little. Although iron and steel were frequently used for tug hulls, wooden-hulled tugs continued to be built until after World War II. And the traditions and camaraderie of wooden-ship maritime life defined the daily relationships and working habits of tugboat men.

Early 1900s

As his photo collection marched backwards toward 1900, Boone pointed out small details that tell large stories of changing technology on the river. Some older photos show boats with running or towing lights that are kerosene lanterns. Tugboat images from the 1930s show pilot houses fitted with the first generation of antennae for the newfangled radio systems that replaced flags, lights and whistle signals as the primary means of communication among commercial maritime craft.

But the historic change most obvious to landlubbers who only casually look at today's tugs involves the "fenders" that hang around the boat's outer edge. These serve as impact cushions between the tugboats and the larger ships they push.

From the 1800s to mid-20th century, tugboats hung their

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| Boone's intricately-detailed paintings of tugboat river scenes are based on his own observations and notes as well as a photo archive containing more than 15,000 images. Above is part of his one-day display at the Historical Society. Larger photo.

| sides with lengths of wood as fenders. Photos show these evolving into mats of manila hawser line roughly braided into thick bumpers. At the nose, a huge mound of hung hawser formed the massive bow protrusion that was the main contact point for a tug pushing a larger-hulled vessel. Visually suggestive of giant buffalo humps, these shaggy mounds were called "bow puddings."

Tires as tug fenders

"In the photos of the 1920s, you begin to see tires appear as tug fenders," said Boone. "The early automobile business was growing and there were a lot of discarded tires to be had for the taking." Through the years, the use of tire rubber to replace rope tug fenders became widespread. Some boats just hung the tires themselves. Others put rope all around the tires. Eventually, it became common to cut up the treads, drill holes and flatten them in place as a solid structure because it made them more stable. Rubber also had the advantage of not absorbing water and freezing in the winter.

But, with a smile, Boone pointed out that some tug old timers who had always used rope had to relearn how to come alongside a ship again after refitting their vessels with tire-tread fenders. "Rope cushioned and the boat 'held' on a larger hull, but when you did the same thing with rubber fenders, the tug tended to hit the ship and bounce off," he said.

Real river rats

And there was also a somewhat gruesome aspect to the older rope fender systems, he said. "After a boat laid out-of-use at a pier for a number of days and the crew took her out again, the first impact with a ship would bring the rats out of the rope fenders." Pier rats, he explained, made comfortable little homes in the bow puddings that readily soaked up the heat of the sun. Then, when the pudding was suddenly squashed

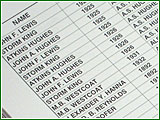

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| Part of a printout from Boone's database detailing all the tugs that operated on the Delaware River each year from 1885 to 1932. He is currently reseaching the period of 1933 to the 1980s. Larger photo.

| against a hull, frenzied pier rats went splashing down into the water or scurrying out onto the tug's deck."

In recent decades, the story of Delaware River tugboating ends sadly. In the 1980s, the collapse of much of the Delaware River's heavy industrial base brought traumatic changes that forever altered the work boat business.

"When I first started in tugs in '71, everybody was making a lot of money, the boats were busy, the food was good," remembered Boone. "But when the river economy started to go, everything else went down with it. Tug crews were cut. First to go was the oiler. Then the cook. You had to bring your own food. Deck hand became an 'unskilled' position. Jobs that had been paying $60,000 were suddenly only paying $25,000."

Industrial collapse

"The river business was drying up around us. Gone were the general cargo ships making weekly calls, replaced with large container ships that called every 4 to 6 weeks. The port once had two raw sugar discharge piers, two iron ore discharge piers, two grain loading and two coal loading facilities, a major steel manufacturer in Fairless Hills, a gypsum plant on the Schuylkill River and another in Cinnaminson. All are now gone."

"It was the end of the way tugboat life had been on the river for a very long time," said Boone who is alternately wistful and upbeat about leaving his job in tugboating to pursue a new career as a self-employed artist and historian.

In many ways, with his sketch pads, paint brushes and light table, he is once again navigating the creek out toward the Delaware and tugboating's golden age. It is an excursion that will allow him to live on the river as it used to be for the rest of his life.

All Rights Reserved © 2003, Hoag Levins

HoagL@earthlink.net

About this Web site

|