BEADED BAGS AND INDUSTRIAL HISTORY

Six Hundred Years of Glittering Commerce

By Hoag Levins ...| ...Feb. 24, 2005

CAMDEN, N.J. -- In many ways, the long history of the beaded handbag parallels that of the Western world's glass and fashion industries. Very few artifacts of Western civilization's material culture reach as far back in time or have remained so consistently popular as the handbag crafted from glass beads.

|

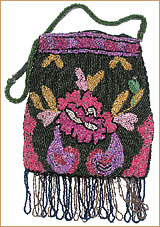

| Photo: Hoag Levins | Bag: CCHS |

Tiny 'seed' beads were one of the earliest glass products ever made and have been used to make purses since the middle ages. The long history of beaded bags is an important thread in the larger story of the Western World's glass and fashion industries. Click for larger view.

|

Beads have always been a premiere product of the glass making trade. In fact, the oldest glass objects ever found are Egyptian glass beads dating to 2500BC.

13th-century Venice

Ancient Rome developed sophisticated glass-working techniques that faded from memory as the dark ages descended across continent. When glassmaking was revived in the 1200s in Venice, one of the first items made there were tiny jewel-like beads that could be stitched, embroidered or wired onto or into the surfaces of purses and other items of clothing and accessories.

Venice emerged as the medieval era's glass-making capital whose rulers jealously guarded the evolving secrets of mass-producing glass objects. The business was a dirty and dangerous one centered around clusters of large wood-stoked furnaces capable of generating the nearly volcanic temperatures required to melt sand.

Threat of death

For reasons of safety as well as secrecy, the Venetian government forcibly moved all its glass-making enterprises to Murano Island in a lagoon north of the city by the early 1300s. There, owners and employees labored under threat of death for revealing any aspect of glass factory methodology to the outside world.

By the 1400s, those Italian craftsmen perfected methods for mass-producing high quality, colored glass "seed" beads, which were round, and glass "bugle" beads which were tubular. The development occurred at the same time European powers were beginning the age of exploration that opened trade routes with then-unknown regions of Asia to the east and North America to the west.

|

| Photo: Hoag Levins |

Here, greatly magnified, is a typical selection of modern glass beads from the Jubili Beads & Yarn shop in Collingswood, N.J. The red tubes in the lower right are hardly thicker than a piece of sewing thread. Click for larger view.

|

The earliest sea- and land-bound European explorers found the lustrous Italian glass beads to be highly prized by the native cultures they encountered across those new frontiers.

In 1492, when Christopher Columbus set out from Spain on his perilous voyage across the western ocean, his three small vessels carried quantities of the Venetian glass product. When the crews sloshed ashore on San Salvador island in the Caribbean, the meeting between Europeans and native Americans began as Admiral Columbus "gave them hawk's-bells, glass beads, and other small things," according to the ship's journal.

New Jersey Indians

In 1609, when Henry Hudson sailed up the eastern shore of what is now New Jersey, he dropped anchor north of Barnegat Inlet in Monmouth County, where he encountered native people and invited them to visit his ship. The vessel's journal records that the Lenape "came aboard us and seemed very glad of our coming, and brought green tobacco leaves and gave us of it for knives and beads."

In 1685, when William Penn signed the treaty in which the Lenape gave up rights to the land that became Philadelphia, the goods used as currency in the deal included "three papers" (envelopes) of glass beads.

Glass was a substance previously unknown to North American native tribes but their culture placed high value on beaded objects for decoration, religious ceremony and commerce. The Lenape of the Delaware Valley had traditionally made bead-like materials from bone, horn, stone, fruit pits and seashells. None of these materials could compare to the sensual, jewel-like qualities of glass beads struck by sunlight.

'Diamonds' of Indian culture

In his history of the Lenape, Herbert C. Kraft wrote that European glass beads became "the diamonds" of native culture,

|

| Photo: Hoag Levins |

In the late 1800s, some Native American tribes began making European-like beaded bags for sale to white consumers. By the turn of the century, both Indian and European bead motifs had borrowed heavily from each other. This beaded purse from the collection of the Camden County Historical Society is from about 1920. Click for larger view.

| valued for their beauty as well as the symbolic meanings assigned to various colors and configurations of beads in Indian ceremonies. He wrote the tiny glass beads "were sewn to clothing, moccasins, and pouches in predominantly floral (Eastern Woodland) patterns. They were strung on sinew and wrapped around the handles of war clubs and on objects of ceremonial use... some were sewn into the helixes of the Indians' ears or were worn in clusters suspended from their ear lobes. Many glass beads were placed into the graves of the deceased, presumably for use in the afterlife."

During their first three centuries of trading with the natives, Europeans used glass beads as a major form of currency, importing massive amounts through ports like Philadelphia. By the 1800s, Venice alone was shipping more than six million pounds of glass beads to North America each year. And that was only part of the picture. By the early 1700s, France, Germany and regions of Bohemia in Eastern Europe had developed glass industries that were shipping additional beads to America.

Benjamin Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette newspaper regularly chronicled glass bead commerce in and around the port of Philadelphia, the colonies' largest city. Throughout the 1700s, waterfront area merchants such as Child & Stiles, Daniel Clark, William Grand and Daniel & George Fundle received incoming cargos of glass beads and offered them for sale. These included "pound beads for the Indian trade" as well as English, Venetian, French and German beads of higher quality for colonists.

Beads and the slave trade

Glass beads also played a significant role in the transatlantic slave commerce. During the 18th century, it is estimated that 40% of the slaves loaded in West Africa were carried to North America in ships home ported in Liverpool, England. Today that city's

|

| Photo: Hoag Levins |

By the 1800s, more than six million pounds of Venetian glass beads were imported into the U.S. each year, and by then Italy was only one of several countries manufacturing the product. In the early 1800s, the U.S. government and merchant traders were delivering beads to American Indian tribes by the ton. Click for larger view.

| Merseyside Maritime Museum chronicles that era and documents glass beads as a common element of the barter goods used by European traders to purchase lots of captured humans in countries like Gambia, Ghana, Senegal and the Ivory Coast.

The same beads were also valued highly enough to make them a war booty for privateers licensed by the Continental Government to attack British merchant ships during the Revolutionary War. One 1778 issue of the Gazette reported a privateer had seized a rich cargo that included "8 chests of arms, 200 brass kettles, and 6 chests of beads."

Tribal beads by the ton

After the Revolution, the new United States government engaged in protracted wars with its Native American nations, systematically conquering and relocating them to reservations, a process that devastated the tribes' social and economic systems. In both the emerging reservation system as well as in the still-free tribal areas of the far west, glass beads were consumed by the ton.

The manifest of a single 1835 boat delivery of supplies to an American Fur Company trading post on the upper Missouri River shows that the cargo included 1,117 pounds of glass beads in nine different varieties.

By the late 18th century, most of North America's Indian groups had been driven from their former hunting lands and many clans sought some measure of economic relief in bead craft. They began designing and handcrafting new sorts of beaded items for sale to affluent white consumers in eastern cities. Initially they copied bead designs from European handbags but quickly evolved their own unique artistic forms.

Victorian bead craft

Meanwhile, throughout Victorian America, the beaded bag fashion fad trickled down in a manner that

|

| Photo: Hoag Levins |

A late-Victorian era beaded handbag from the collection of the Camden County Historical Society. Click for larger view.

| made glass beading a major part of the domestic textile arts that played a central role in the daily home life of middle-class women and their female children.

Women's magazines of the day regularly published detailed instructions and complex schematics for creating glass bead patterns on handbags, dresses, bonnets, negligees, pincushions, sofa cushions, table mats, watch cases, bracelets, brooches, jackets, capes, and mourning hats, shawls and wreaths. The latter group consisted entirely of jet-black glass beads.

Beaded bags' popularity declined in the final decades of the 1800s only to undergo a wild resurgence of popularity shortly after the turn of the century. The writers of the New York Times, who were the elite arbiters of fashion in the 20th-century city second only to Paris as an international fashion center, chronicled the trend that occurred as World War I exploded across Europe. Excerpts from the Times fashion reporters:

20th-century fashion

Oct. 4, 1914 -- "These bead bags carry us straight back fifty years to the days of hoop skirts and muslin tuckers, lace mits and pantalettes. They are, in spirit of their old-fashioned look and their ancient design, quite the smartest thing in handbags, and the fashionable woman who has been fortunate enough to get a frock from Cheruit, Worth or one of the other war-troubled French dressmakers feels that her modern French toilet lacks the finishing touch unless she has an old-fashioned bead bag."

Jan. 24, 1917 -- "The difficulty of securing sufficient quantities of beads is hampering makers of women's handbags in their efforts to meet the heavy Spring demand."

Aug. 15, 1916 -- "This has been the season of fancy hand bags. Every woman must have a half dozen and new designs are coming in all the time. The beaded bags which have been so popular in France are still the thing here. There are many ways in which the beads are used and some of the bags reproduce the shapes of our grandmother's days."

Sept. 16, 1918 -- "Some very fine beaded bags for women are now being made in this country. The many difficulties in the way of obtaining the Paris article have tended to spur domestic manufacturers on to increase effort... one of the chief difficulties is that of obtaining labor sufficiently skilled to duplicate French workmanship. Another handicap is in the scarcity of certain colored beads."

Dec. 17, 1919 -- "There are some buyers as well as sellers of beaded bags who profess to see a slackening of demand for these goods. Imitations such as stenciled velvets, have sprung up... but there will always be a call for those beaded bags which surpass in design in workmanship."

Aug. 9, 1925 -- "A craze for purses and hand receptacles in which to carry the proverbial 'everything but the kitchen stove' which women are wont to tote on shopping expeditions is just now apparent, and in the form of beaded bags, the purse is reviving its former glories."

And since that time, eighty years ago, the little beaded bag has remained a much beloved fashion staple of generations of modern American women as well as the manufacturers and craftsman around the world who continue to make them.

~ ~ ~

|