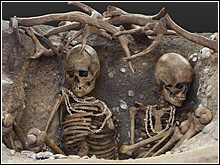

Commemorative eating and drinking customs at funerals go back so far in time that Paleolithic humans are believed to have dined on the corpse itself before they buried it. Those ancestors -- we now know them as "cave men" -- were the first humans to perceive some higher meaning in death and to ceremonially entomb their dead. It's likely that eating a bit of a deceased loved one was an effort to both honor and incorporate their essence into one's own. Anthropologists believe this grisly habit evolved into the somewhat more

Photo: Rama

|

| Reconstruction of a prehistoric grave excavated in France. Paleolithic humans were the first to ceremoniously bury their dead. |

civilized mourning practices throughout medieval Europe and ultimately gave rise to the "funeral biscuits" so popular in the Victorian age.

Emerging from the Middle Ages in old Germany, for instance, was the funeral tradition of eating "corpse cakes" that symbolically mirrored the act of eating the deceased. After the body had been washed and laid in its coffin, the woman of the house prepared leavened dough and placed it to rise on the linen-covered chest of the corpse. It was believed the dough "absorbed" some of the deceased's personal qualities that were, in turn, passed on to mourners who ate the corpse cakes.

Similar traditions were found in Hungary and other parts of central Europe where various sorts of food and drink were placed close to the corpse for an hour to "absorb" the virtues of the dead individual before being consumed. In a tobacco-based version of this concept, in some areas of Ireland, a bowl of snuff was placed on the chest of the dead person or the lid of the coffin, and each of mourners was expected to take a pinch.

Perhaps the most colorful commemorative funeral food ritual of this old genre was that of the "sin-eater" in Great Britain and Ireland during the 17th and 18th centuries.

The local sin-eater was a reviled person of the lowest social status -- not unlike the untouchables of

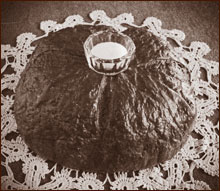

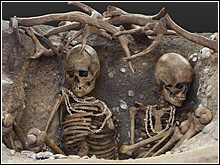

|

| Sin-eaters ate salt and bread laid out on the corpse's chest. |

India or burakumin of Japan -- who was paid a pittance to attend the wake and eat bread and salt from a plate or bowl resting on the chest of the deceased. In doing so, he was believed to be consuming and transferring the sins of the dead to himself, allowing the departed soul to enter heaven rather than be forced to wander the earth to atone for wicked deeds. Period accounts indicate that once the sin-eater finished the plate, he was often kicked, punched and otherwise abused by the crowd as he scrambled to escape the gathering. After the sin-eater departed, family members stood on one side of the coffin and handed chunks of "arvel" or "arvil" cake across the corpse to mourners. The practice traces back to the Nordic tradition of hoisting bowls of "heir ale" at funerals to toast the oldest male's assumption of the family property and power. The English "arvel" or ale cakes were often washed down with hearty draughts of spiced ale or port before the pallbearers carried the body to the burial site.

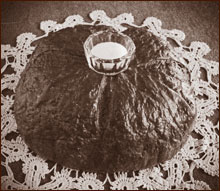

Affluent individuals of the era sometimes used "mazer bowls" in sin-eater rituals. These are a type of drinking vessel

|

| Wealthy individuals sometimes used mazer bowls for sin-eating rituals. |

that originated in early Nordic culture. Made of turned maple wood, often eight inches or more across, the bowls usually had bands of metal around their rims and were often decorated with rich tooling on the wood and metal. People fixated on the details of their future funeral would sometimes commission special mazer bowls from which the sin-eater would consume bread, salt and cheese. After the burial, the bowls became a family heirloom and memorial. By the late 18th century, commemorative funerary food traditions were becoming more refined in European and U.S. culture and focused on the offering of small cakes to those who came to wakes and burials. These were known as "funeral biscuits" (and came to be called "funeral cookies" by the late 19th century in the U.S.). Although they varied widely in size, shape and consistency, in spirit they were all the same.

The British upper crust tended to favor the use of the sponge cake-like Lady Finger biscuits sometimes as wide and long as a modern hot dog roll. These were wrapped in plain paper held together with a daub of black sealing wax.

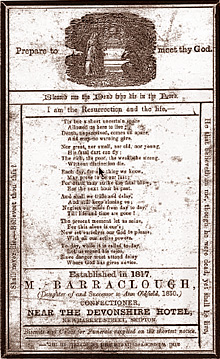

In the Yorkshire and Lincolshire sections of England, they were called "burying biscuits." In an 1802 letter,

|

| A wrapper from the British Lady Finger-type funeral biscuit. Larger |

one local described his earlier experience at a Yorkshire "funeral of the richer sort": "They had burnt wine and a paper with two [Lady Finger] biscuits sealed up to carry home for their families. The paper in which these biscuits were sealed was printed on one side with a coffin, cross-bones, skulls, hacks, spades, hour-glass, etc... sealed with black wax." The common people in the Colonies tended toward dense shortbread funeral biscuits flavored with molasses, ginger or caraway. Resembling modern-day cookies in size and shape, these were often formed in hand-carved wooden stamping molds that embossed a cross, heart, death's head or cherub on their tops.

In her study of Colonial-era funeral practices, historian Jacqueline Thursby describes Pennsylvania customs in Montgomery County near Philadelphia:

"A young man and young woman would stand on either side of a path that led from the church house to the cemetery. The young woman held a tray of spirits and the young man a cup. As mourners passed by, they received a [biscuit] from the maiden and a sip of spirits from the young man. A secular communion of sorts, these ritual behaviors transcended countries of origin and melded a diverse young nation with the common cords of death, mourning and tradition.

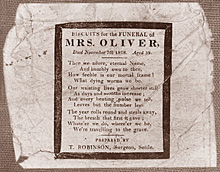

|

| It some places, it was common to wrap funeral biscuits in printed death notices. Larger |

The funeral biscuit served as part of a code representing understood messages of mourning, honor and remembrance." Diaries from Hudson Valley Dutch communities include recipes for doot coekjes or "death cookies" that were "large as saucers" and designed to be eaten with hot spiced wine. One recipe called for 50 pounds of flour, 20 pounds of sugar and 10.5 pounds of butter for 300 cookies delivered to the funeral in bushel baskets. Mourners were offered sweet wine in which to dunk and soften the hard-textured confections.

In the Victorian Age, funeral biscuits, along with all other customs related to death and mourning, became more formalized and baroque. Like wedding cakes, funeral biscuits were a staple of the bakery business, and competition for customers was brisk. Some bakers' newspaper ads addressed the suddenness with which most people had to organize funeral details and promised "funeral biscuits made to order on the shortest notice."

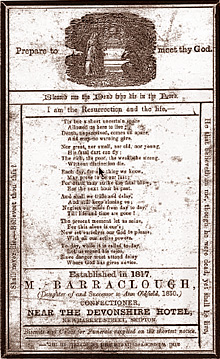

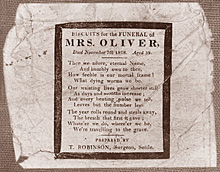

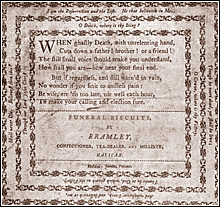

The commercial biscuit wrappings were ornately printed with bakery advertisements as well as uplifting biblical quotes

|

| Victorian Age funeral biscuit wrappings were often printed with Biblical verse and poetry. Larger |

and poems. Like church holy cards, they served as a keepsake of the event itself. The rapidly-evolving technology of printing enabled bakers to offer increasingly detailed designs and custom messaging on the wrappings. Essentially, the card-like printed death notice merged with the funeral biscuit to become its wrapping. Small sacks of the confections were often sent around to family and friends as death notices that one could read as well as eat. At the height of the Victorian Age -- around the same time as the U.S. Civil War -- the Victorian poetry on funeral biscuit wrappings was as maudlin and overwrought as the Victorian garden cemeteries to which the dead were dispatched. A sample:

When ghastly Death, with unrelenting hand,

Cuts down a father! brother! or a friend!

The still small voice should make you understand,

How afraid you are -- how near your final end.

But if regardless and still warned in vain,

No wonder if you sink to endless pain:

Be wise before it's too late, use well each hour

To make your calling and election sure.

And, another:

Thee we adore, eternal Name,

and humbly bow to thee,

How feeble is our mortal frame!

What dying worms we be.

Our wasting lives grow shorter still,

As days and months increase;

And every beating pulse we tell,

Leaves but the number less.

The year rolls round and steals away,

The breath that first it gave;

Whate'er we do, where'er we be,

We're traveling to the grave.

By the time of World War I, it was funeral biscuits that had traveled to the grave, fading from use and memory in mainstream European and U.S. society. The Victorian traditions they were part of were replaced by today's mass-market funeral home chain services and the catering halls and restaurants that so often seem as empty of spirit as they are full of unmemorable food.

|