A LIVELY LOOK AT THE HISTORY OF DEATH

Exploring the Architecture and Rituals of Civil War-Era Mourning

By Hoag Levins

CAMDEN, N.J. -- Death, the topic, descended on the Camden County Historical Society yesterday but it wasn't a morbid or unhappy

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| Dressed in the formal mourning clothes of a nineteenth-century Civil War widow, Jane Peters Estes gave a presentation on Victorian death customs. Larger photo. | event. In fact, the Fall Festival program focused on nineteenth-century cemetery architecture and mourning customs was as enjoyable as it was educational.

Historic cemetery

The Society's headquarters in Parkside is located just a stone's throw from the heavily wooded grounds of the 117-year-old Harleigh Cemetery and the two facilities cooperated in the day's activities.

"Death records and the social rituals surrounding death are among history's most important touchstones," said Society president Richard Pillatt. "And here at Harleigh, in Camden County, we have an extraordinary example of a Victorian-era garden cemetery that was actually designed as a park -- a place of public entertainment."

Visitors alighting from a bus provided by the County Freeholders seemed to agree. On a crisp, clear day amidst trees flared red and yellow they were taken in tow by Harleigh manager Chris Mojica and operations manager Donna DiFiore, both dressed in the period costume of 1880s funeral directors.

'Grave Matters'

The tour through winding roads of temple-like mausoleums, angelic statuary and soaring stone monoliths ended with a bus ride back to the Historical Society's auditorium. There, Jane Peters Estes, veiled and in formal black mourning attire, waited to begin a presentation entitled "Grave Matters."

An authority on death customs in Civil War-era America, Estes spoke of the surprisingly complicated protocols of mourning behavior and dress of the period.

Covered mirrors

"The Victorians had a lot of superstitions associated with death. When there was a corpse

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| Harleigh, Camden's Victorian cemetery, was a sunny tableau of fall foliage and marble statuary. Larger photo. | in the house you had to cover all the mirrors," she said. "And if a mirror in your house was to fall and break by itself, it meant that someone in the home would die soon. When someone died in the house and there was a clock in the room, you had to stop the clock at the death hour or the family of the household would have bad luck. When the body was taken from the house, it had to be carried out feet first because if it was carried out head first, it could look back and beckon others to follow it into death."

Graveyard revolution

Views and practices related to death and burial in America paralleled those of Europe and began to change significantly in the early 1800s, she explained. Probably the most dramatic manifestation of this change was the graveyard itself. In London and Paris, the concept was revolutionized with the design of elaborate "garden cemeteries" that were lushly landscaped burial grounds as well as public parks. The trend quickly took hold in the U.S. with the construction of facilities like Laurel Hill along the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, and Harleigh along the Cooper River in Camden.

Socially, decorum demanded that family members adjust their behavior and dress for years after the death of a close relative.

"We have worn particular clothing to mourn our dead all the way back to the

Photo: National Archives

|

| This 1865 Civil War photo shows women in full mourning clothes (lower right) walking through the ruins of Richmond, Va., capital of the defeated Confederacy. Larger photo. | 1600s," said Estes. "But it was in the 1830s and 1840s that we saw mourning become an art form. There were many books written on the subject of how to mourn, what to wear, when to wear it. Of course, when Prince Albert died in 1861 and the Queen of England went into mourning, society on both sides of the ocean took on mourning with a vengeance.

That same year, the American Civil War began and death on a massive scale touched communities and families North and South. Mourning became a central fact of wartime life. Formal black mourning clothes -- even items of underwear and accessories like gloves and handkerchiefs had to be black -- were a society-wide necessity.

"The Civil War resulted in approximately 600,000 casualties. In the state of Alabama alone, there were over 80,000 widows -- 80,000 women dressed for mourning as I am today," Estes told the audience.

Protective veil

"If I were to go out on the street in mourning in the 1860s, I would have covered my face with the veil. One reason is that it would shield the fact that I had been crying. You wouldn't see the tears of the

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| Chris Mojica, manager of Harleigh Cemetery, leads the tour to Walt Whitman's tomb. Larger photo. | mourner. But another of the superstitions they believed in back then was that spirits of the departed would hover around those they loved. And if a passerby looked directly on the mourner's face, that spirit might attach itself to that person. So, the veil was a protection for the wearer as well as a protection for others."

"Mourning clothes were something you needed quickly when there was a death in your family," she said. "As a result, mourning garments became the first off-the-rack clothing you could buy. Remember, this was a time when most clothing was made at home."

"You could either go to a place that sold mourning clothes and buy them, or take everything you had to a merchant who would dye them all black. If you were poorer than that, you would put your own clothes in a large pot in your back yard and dye them black. The reason you did it outside was that black dye was very pungent smelling. The diary of one woman from Virginia in 1864

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

| The design, production, sale and repair of mourning clothing and acoutrements was a major industry in 19th-century America. Typical products from the era were on display. Larger photo. | mentions that 'the entire town smells of the dye pots'. Unless you know about mourning customs you can't understand what that meant. Basically, everyone in that town was mourning and changing their clothing color for someone. They couldn't afford to buy new clothes and they couldn't afford to have clothes dyed by someone else. They were doing it themselves."

In another area of death lore, she pointed out how the anguish and animosity of the Civil War was literally recorded in stone in some burial grounds.

Historic gravestones

"I found the gravestone of a Union Soldier who had the misfortune of dying in Fredericksburg, Va.," she said. It read:

"They came from the north to our southern land to venge their fire and make their brand. But this lonely, desolate forgotten spot is all this Yankee bastard got. Come not again to feed our soil but leave us alone to our peace and toil. And let this place in remembrance be, a fitting end and a dread to thee."

Another curious and widespread concern in the nineteenth century was the fear of being buried alive. "This was a superstition that so permeated society that even Mary Lincoln, a relatively well-to-do, well-educated woman, shared in her final instructions her fear of this. She wrote,

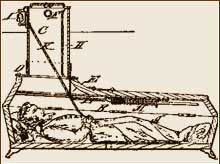

|

| This is a U.S. patent drawing for a coffin alarm and escape system from the 1860s. | 'I desire that my body shall remain for two days with the lid not screwed down.'"

Coffin Alarms

"Because of this fear," Estes said, "they developed a coffin alarm. This was a bell attached to the headstone with a chain that led down into the coffin to a ring that went around the finger of the deceased. So, if you were to wake up and find yourself accidentally buried, you could pull on the chain and ring the bell in the cemetery yard.

"Can you imagine being the graveyard caretaker working late one night and hearing one of those bells ring?" she asked.

All Rights Reserved © Hoag Levins

HoagL@earthlink.net

About this Web site

|