THE GANG THAT KILLED ABRAHAM LINCOLN

A Kidnap Conspiracy That Turned Into Murder

By Hoag Levins

CAMDEN, N.J. -- In the century and a half since it happened, populist history has largely boiled down the assassination of Abraham Lincoln to the story of a single perpetrator: John Wilkes Booth.

Photo: National Archives

|

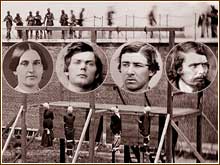

| Four of the eight convicted for participating in the conspirary to assassinate Lincoln in April of 1865 died on the gallows three months later. Larger photo. | But in his appearance at the Camden County Historical Society, Lincoln scholar Hugh Boyle made clear that the real story is a sprawling epic.

It involves a gang of Confederate operatives and sympathizers that first plotted to kidnap the President and, when that failed, decided to murder not only him, but the Vice President and Secretary of State as well. Their goal was to decapitate and destabilize the federal government in hopes of forcing a settlement to the war that would avoid the South's total defeat. In the end, they managed to kill Lincoln and seriously injure Secretary of State William Seward.

Four executed

The gang leader -- 27-year-old John Wilkes Booth -- was tracked down and shot to death by Union soldiers in Virginia. Eight others were convicted of being conspirators with Booth. Four were sentenced to death and hung, including the first woman ever executed by the U.S. government. The other four were sent to a remote prison island off the coast of Florida.

"School children today learn maybe one-tenth of the actual story of the Lincoln assassination," said Mr. Boyle, speaking in the Historical Society's Boyer Auditorium.

Photo: Hoag Levins

|

|

Hugh Boyle is President of the Delaware Valley Civil War Round Table and the April 1865 Society. A member of the faculty of the Civil War Institute at Manor College in Jenkintown, Pa., he is also on the board of directors of the GAR Library and Museum, where he curates the Lincoln exhibits. Larger photo. | "For instance, author Vincent Bugliosi recently put out a book that documents the Kennedy assassination and it runs to more than 1,500 pages. But if you tried to put together a similar book on the Lincoln assassination, it would be twice that size. That's how many people were involved in the investigation."

1865, the last year of the Civil War, was a time of extreme desperation for the slave-state Confederacy and its supporters. Vast stretches of the South's plantations, ports, railroads, and industrial facilities lay in total ruin. The probability of total defeat was now obvious.

'A time of terrorism'

"It was also a time of terrorism that we've largely forgotten," said Boyle. "We saw the beginnings of chemical and biological warfare in this period. For instance, Dr. Luke Blackburn of Kentucky collected large quantities of clothes and blankets from a Yellow Fever outbreak and shipped them to Washington in hopes of triggering an epidemic there.

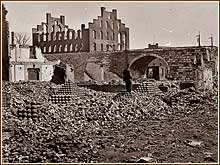

Photo: National Archives

|

| By 1865, the South was a vast swath of utter destruction. Shown here are the remains of what was the State Arsenal in Richmond. Larger photo. | Other people were trying to poison the water supplies of northern cities. Still others were setting fire to hotels in New York. It was a time of massive upheaval, great danger and high emotion for the South, so the idea that someone might be thinking about attacking the President or other high government officials was not a crazy one in the atmosphere of the times."

The frustrations and angst of the Southern cause came to a boil in April of 1865. Its capital, Richmond, Va. -- now a burned out hulk of a city -- was captured and occupied by Ulysses S. Grant's forces on April 3. The first Union Army units that marched into the city were U.S. Colored Troops.

Six days later, Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia surrendered and was disarmed at Appomattox. Three days after that -- April 11 -- President Lincoln, standing in a second-story window of the White House, spoke to a huge crowd in a city gone wild in celebration of the Appomattox surrender.

Lincoln's last speech

But among those listening in that crowd were John Wilkes Booth and 21-year-old Lewis Thornton Powell.

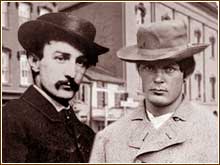

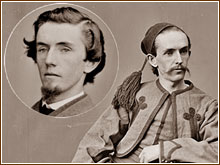

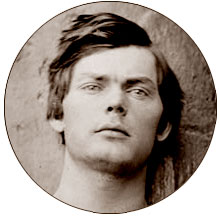

Photos: National Archives

|

|

John Wilkes Booth (left) and Lewis Thornton Powell were enraged by the President's White House speech on April 11. Three days later, Booth killed Lincoln in Ford's Theater while Powell tried to kill Secretary of State William Seward in his home. Larger photo. | Booth was one of the country's most famous actors and an ardent supporter of the Confederacy. His young companion, Powell, was a Confederate army veteran and a second cousin of Confederate general John B. Gordon, head of Georgia's Ku Klux Klan.

Powell, who enlisted at age 17, fought at Antietam, Chancellorsville, Murfreesboro and Gettysburg, where he was wounded and taken prisoner of war. He escaped his captors and, using the alias Lewis Payne, joined a Confederate guerilla-warfare unit conducting raids behind Union lines.

Under circumstances that have never been fully documented, Powell/Payne suddenly left that unit to work with John Wilkes Booth in a plan to kidnap Abraham Lincoln. It was strongly believed -- but never conclusively proven by Union military investigators -- that a Canadian-based arm of the Confederate Secret Service was behind that kidnap plot.

Lincoln kidnap plot

"The plan," said Boyle, "was to kidnap Lincoln, take him to Richmond and use him as a bargaining chip to win the release of all the Confederate prisoners being held in Union prison camps."

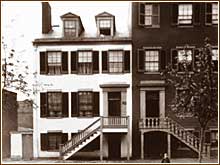

Photo: National Archives

|

|

Mary Surratt's boarding house in Washington was a meeting place for Confederate spies and operatives, including those planning to kidnap Lincoln. Larger photo. | In March of 1865, Booth, Powell and a number of other conspirators prepared to seize Lincoln as he traveled to attend a play at a hospital near the Washington cottage that served as his Presidential summer home. The gang took up position on the road to the hospital but their venture failed when Lincoln changed plans and attended another capital function instead.

A month later, as he and Powell stood in front of the White House on April 11, Booth decided to escalate the plot from kidnapping to murder.

"Booth was enraged as he listened to Lincoln talk about how Black men should have the right to vote in that speech," said Boyle. "We believe that Booth made up his mind about the assassination on that day. We know he turned to Powell and said, 'That's the last speech Lincoln will ever give.'"

The war wasn't over

"Its important to understand that neither the fall of Richmond nor the surrender of Lee at Appomattox ended the war," said Boyle. "A lot of people today aren't clear on this and it's an important fact because it played a big role in the ultimate fate of the conspirators. Confederate general Joe Johnston was still fighting Sherman down in the Carolinas. The war wasn't over."

At the time he began planning the earlier failed kidnap attempt, John Wilkes Booth recruited a number of people to help. Powell, the battle-hardened Confederate veteran, was crucial to the plan because of his strength and size.

"Booth knew he needed a big, strong guy, about six-foot-five or so," said Boyle. "Why? Well, if you're going to kidnap a President who was six-foot-four, you better have a guy his size.

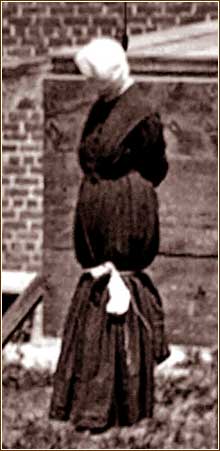

Photo: National Archives

|

|

Dead on the gallows is Mary Surratt, the first women ever put to death by the Federal Government. Larger photo. | Powell was enormously strong and he also developed the strangest and most dedicated allegiance to Booth of all the conspiracy group members."

That group also included:

- John Surratt, 21, a Confederate spy and courier and the son of Mary Surratt.

- Mary Surratt, 42, proprietor of a Maryland tavern and a Washington boarding house that served as meeting places and safe houses for Confederate spies and couriers.

- David Herold, 23, a Washington pharmacist and former schoolmate of John Surratt.

- George Atzerodt, 30, owner of a down-and-out carriage painting business in Port Tobacco, Va. He knew the southern Maryland waterways, back roads and woods and shuttled Confederate couriers and spies back and forth across the Potomac. A heavy drinker, he was introduced to Booth by John Surratt.

- Dr. Samuel Mudd, 32, a Maryland physician, tobacco farmer, slave owner and member of the underground anti-Union partisans in Maryland. In 1864 Mudd joined Booth in the kidnap plan and introduced the actor to John Surratt.

- Samuel Arnold, 31, a Confederate Army veteran and former schoolmate of Booth's.

- Michael O'Laughlen, 25, another former schoolmate of Booth's who was a member of a secret Confederate organization involved in sabotage.

- Edmund Spangler, 40, a Ford's Theatre employee who was unwittingly entangled in the assassination by Booth.

Three assassinations planned

During the 72 hours after he made his assassination decision on April 11, Booth hurriedly organized Powell, Atzerodt and Herold for action on April 14. Booth was to kill Lincoln at Ford's Theater. Powell was to kill Secretary of State William Seward at home and Herold was to assist him. Atzerodt was to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson. All were to strike at 10:15 p.m.

"Before he went into Ford's theatre," said Boyle, "Booth stopped in a saloon along the side of the theater. As he was having a drink, someone in there recognized him and said, 'You're not

Photos: National Archives

|

|

The Derringer Booth used to murder the President and the Bowie knife Powell used in his attempt to kill Secretary of State Seward. Larger photo. | the actor your father was,' Booth's answer was 'When I leave the stage, I'll be the most famous man in America.'" A short time later, sneaking into the President's theater box, he shot Lincoln in the head at point-blank range.

Simultaneously, Lewis Thornton Powell and David Herold arrived at the home of Secretary Seward, who had helped write and had signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Herold remained outside with the horses as Powell went to the front door. Carrying a Whitney Navy revolver and a 12-inch Bowie knife, he pushed past a servant and was confronted on the stairs by Seward's son, Frederick. Powell tried to shoot him in the head at close range but the revolver would not fire, so he beat him across the head with it. As he entered the elder Seward's room, Powell fought with both a male nurse and Seward's daughter before leaping on the bed and slashing the Secretary of State multiple times with the Bowie knife. On his way out of the building, he fought with both Seward's second son and a State Department courier, whose throat he slashed.

Photos: National Archives

|

|

Powell slashed Seward around the face and neck multiple times and believed him dead. But, although heavily disfigured, the Secretary of State survived. Larger photo. |

But once out on the street, he found himself alone. Herold, who was supposed to guide Powell out of the city, had heard all the noise and run away. Powell wandered around Washington for days, hiding in the Congressional cemetery at night, where he slept in a tree.

Meanwhile, George Atzerodt, armed with a gun, had checked into Washington's Kirkwood House where the Vice President was also staying. Before the appointed attack time, Atzerodt began drinking in the hotel bar. Drunk and unable to bring himself to actually carry out the murder, he wandered the streets of the capital for the rest of the night.

Booth's escape

Fleeing Ford's Theatre on his horse, Booth met up with David Herold and rode to Mary Surratt's tavern in Maryland, where guns had been stored. Now armed with a carbine rifle, the two rode to the farm house of Dr. Samuel Mudd for treatment of Booth's leg, which had been injured during his escape. For the next twelve days, Booth and Herold hid out in various locations in southern Maryland before they crossed the Potomac and took refuge in the barn of a farm owned by Richard Garrett in Virginia.

Photos: National Archives

|

|

Initially recruited for the Lincoln kidnap plot, Dr. Samuel Mudd aided Booth during his escape immediately after the assassination of Lincoln. Larger photo. | At the same time, they became the subjects of the largest manhunt in North American History.

A Union Army cavalry unit finally tracked them to Garrett's, surrounded the barn and set it afire to force the fugitives out. Herold came out peacefully and surrendered. Booth refused to come out and brandished the carbine inside. Aiming through a crack in the barn boards, Union sergeant Boston Corbett shot him through the neck. Booth died hours later on the front porch of Garrett's house.

The massive military and law enforcement investigation that took Herold into custody had also arrested Lewis Thornton Powell, George Atzerodt, Mary Surratt, Dr. Samuel Mudd, Samuel Arnold, Michael O'Laughlen and Edmund Spangler.

'Ninth conspirator'

Curiously missing among the arrested was the man many called the "ninth conspirator," Confederate agent John Surratt. Evading the dragnet, he fled to Canada, took a ship to England and made his way to Rome. There, he disappeared from view by changing his name and joining the military unit that protected the Pope. This unlikely tactic was made possible by the fact that the Surratt family were devout Catholics and had had friendly contacts in church circles.

Photos: National Archives

|

|

Confederate spy John Surratt fled the country and hid out in Rome where he joined the military unit that protected the Pope. Larger photo. |

All eight went on trial before a military tribunal whose nine judges included some of Lincoln's top generals.

"The issue of using a military tribunal rather than a civil court was as controversial back then as it continues to be today," said Boyle. "But that's what Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was determined to do. U.S. Attorney General James Speed wrote the decision that basically concluded that the war was not over when Lincoln was killed. So, the conspirators did not just kill a private citizen serving in the Presidency. They killed the Commander in Chief of the armed services during time of War."

Death by hanging

The two-month trial heard testimony from more than 300 witnesses and generated a transcript of nearly 5,000 pages. In the end, four of the eight -- Lewis Thornton Powell, Mary Surratt, David Herold and George Atzerodt -- were sentenced to death by hanging. The other four -- Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlen, Samuel Arnold and Edmund Spangler -- were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Forty eight hours after President Andrew Johnson approved the sentences, four of the conspirators were hung.

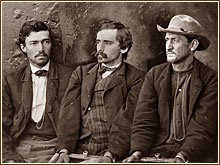

"Why did they split up the eight into four who went to jail and four sentenced to death?,"

Photos: National Archives

|

|

Along with Dr. Mudd, three other conspirators were sentenced to life imprisonment: (left to right) Confederate Army veteran Samuel Arnold, Confederate operative Michael O'Laughlen and hapless stagehand Edmund Spanger. Larger photo. | said Boyle. "My belief is that each one of the four who went to the gallows was directly involved in something on the day of the President's assassination."

"The other four were shipped off to Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas off Florida, " said Boyle. "This was a military fort that had been turned into a prison. Inmates who broke the rules often had to carry around 30-to-50 pound iron balls all day. Really troublesome prisoners were hung up by their thumbs for periods of time."

In 1867 an epidemic of Yellow Fever swept through the tightly-packed prison population killing Michael O'Laughlen and many other inmates, guards and the prison's only physician. Dr. Samuel Mudd, the inmate, was pressed into service to administer to the sick during the emergency and did an outstanding job. As a result, the surviving warden and military guards later wrote letters to President Johnson asking for mercy for Mudd. Just before he left office in 1869, Johnson issued a Presidential pardon for Mudd, Arnold and Spangler.

The one that got away

"The one that got away -- John Surratt -- did avoid capture for a while in Rome, but eventually someone recognized him," said Boyle. "He was arrested, but escaped and took a ship to Alexandria, Egypt, where authorities were waiting for him. He was sent back to the U.S. and tried for the same crimes as his mother. But this time it was a civil trial that resulted in a hung jury. John Surratt got off and lived until 1916."

A bizarre modern-day footnote to this assassination story surfaced in 1991 when the skull of Lewis Thornton Powell was discovered in an attic storage bin

Photos: National Archives

|

|

The skull of Lewis Thornton Powell was found in the Smithsonian Institution in 1991. | at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. In 1865, Powell had been buried in a grave next to the gallows where he was executed. But later, his body was moved to other storage or grave sites at least four times. It's believed that the skull became separated from the body during one of those moves and ended up in the Army's medical museum. In 1898, that military facility passed it on to Smithsonian, where it was inadvertently mixed in with a collection of Native American bones -- and forgotten for nearly a hundred years.

In 1994, Powell's skull was claimed by an elderly family member who had it buried in Geneva, Fla., near his mother's grave.

All Rights Reserved © 2009, Hoag Levins

HoagL@earthlink.net

About this Web site

|