|

HAMMONTON, N.J. -- A dozen years after their 100-home village on the heavily-wooded grounds of Ancora Pychiatric Hospital was abandoned and marked for demolition, dozens of the children who grew up in the unique community over its nearly 45-year existence gathered for their first reunion at a Hammonton parish hall this summer.

Sparked by a Facebook page created by former 'Ancora kid' Kathy Longo of Newtonville, NJ, fellow Ancorans came from as far away as Boston and Arizona to attend the afternoon event that was a nostalgic gabfest of old photo albums, cold beer, homemade wine and hugs all around. Held in the Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Society hall a few miles from the Ancora site where they all once lived and/or worked, the afternoon focused on the

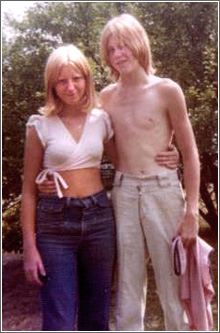

|

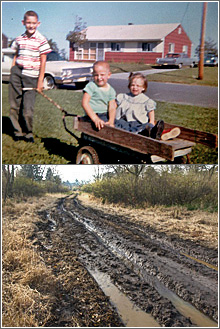

| For four decades, the Edgewood homes community adjacent to Ancora Psychiatric Hospital was a vibrant slice of 1950's Americana (above). Today (below), only muddy ruts of what used to be Park Drive traverse the site of the totally demolished village. Larger |

details of life in Edgewood, the oval tract of homes erected in 1955 to house workers for the newly-opened psychiatric hospital. The children grew up in that isolated Pinelands area with the sprawling hospital and an adjacent state prison unit as their neighbors. It was one of New Jersey's least known and most unusual residential communities; a place where growing up was, according to Leslie Morgan, who came of age there, a time of "innocence and insanity."

The Ancorans, anticipating this reunion day for months, brought enough food and drink for a small army -- meatballs in gravy; baked ziti; a deli platter; potato and macaroni salad; deviled eggs; pretzels and chips for munching. Fresh fruit platters; a pineapple upside down cake; layer cakes; even a sheet cake for Ancoran Gary Bergh's birthday. There were cases of soft drinks and water. And plenty of BYO's -- ice-cold beer in coolers; slushy drinks that looked like water ice but packed a wallop; even homemade wine from local Ives grapes.

First reunion

Most entered the hall tentatively, not quite knowing what to expect. But within seconds, faces lit up and arms opened wide as the 'Ancora kids' recognized old friends. Photo albums were passed around, every image prompting a story or memory as in, "Oooh, he was my first crush."

The children of Ancora Psychiatric Hospital employees, their childhoods were, for the most part, not that different from those of most South Jersey kids. Their parents operated the heavy equipment

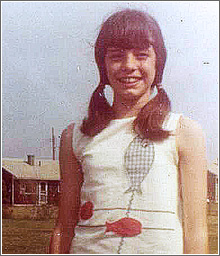

|

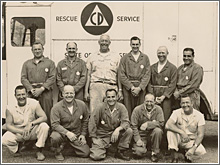

| The 'Ancorans' were the children of the workers who operated the mini-city of Ancora hospital. Here is the crew of Ancora's Civil Defense team, part of the early 1960s cold war readiness program. Larger |

that cleared the land for the new hospital and its 100 homes in 1955. They taught in the children's unit, and were the telephone operators, plumbers, cooks, firemen, security officers, maintenance personnel, medical record administrators, doctors and nurses who kept the hospital running. And one parent, Bea Bergh, babysat for other employees' children. Ancoran Marjorie Avellino Sherrard joked that whenever anyone asked how her parents met, she answered, "At a psychiatric hospital." $40 a month, no utility fees

They grew up in the self-contained development of prefab Edgewood Homes manufactured by Trilco Terminal in Toms River that had the cookie-cutter look and feel of other post-WWII 'Levittown' -like housing tracts. Ross Morgan, administrative assistant to the medical director of Ancora Psychiatric Hospital when it first opened, moved his family into a three-bedroom rancher on a large corner lot in 1956. Lisa Morgan Carney remembers that her parents, like other employees, paid rent only -- about $40/month and no utilities -- for decades.

Ask any Ancoran to describe his or her house and the first thing they say is "tiny." Looking back, Deborah Rossetti-Daniels is reminded of the "little boxes made of ticky tacky" lyrics of a 1960s

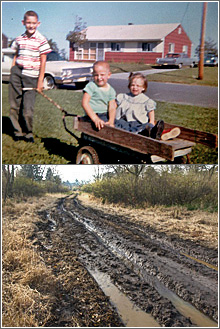

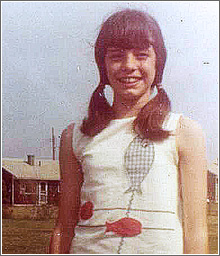

|

| Kathy Longo today (left) and as a young girl (right) growing up in the Edgewood village adjacent to Ancora Psychiatric Hospital. Longo is the creator of the Facebook page 'Growing Up in Ancora' and, along with her brother Dave, the organizer of the first reunion of Ancorans. Larger |

song. Then she fondly remembers the day she, her mother and two sisters moved in. "My mom drove into the driveway in her light blue Studebaker with all three of us in the back seat. The house was red and freshly painted -- it looked great to us." Kathy Longo remembers their colors -- red, brown, green and gray -- and can tell you who lived where by their house color. "John lived in red, Lisa in brown, Barb in green, Beth in red, Butch in green, Skip in red, and us in brown."

Two- to three-bedrooms with one bath, Ancoran Lee Guldin described the Edgewood Homes as small, but ahead of their time. Built on a concrete slab, "they had a furnace in the center of the house and black tiled floors that were always heated because the duct work spread out like a spider web through the hallways and into each room, radiating heat from the tiles."

Small but cozy homes

The black tile floors were made of asbestos, as were the pipe wrappings that helped keep the little houses warm. The windows were drafty; there wasn't much insulation; they were "hot as hell" in the summers; and, as Barbara Pinkos George recalled, "You couldn't put a marble on any table in the house without it rolling off." Despite all that, to Ancoran Stephania Helfand Maslinski, those tiny, poorly-built prefabs "were cozy -- they were home."

Just across the road, Ancora was also home to a sprawling psychiatric hospital

|

| In what some remembered as a daily environment of 'innocence and insanity,' Ancoran children routinely interacted with hospital patients like those shown in this late 1950s' photo. Larger |

on 650 acres of pinelands. Designed to house 2,500 patients, its buildings were connected by underground tunnels used to transport patients and goods between buildings, especially in foul weather. But, as Jacque Wooton-Carver recalled, they were also designed as bomb shelters. "I went to a class where we were taught to help people get into the shelters; I think I was about 16. Remember, this was back in the '60s, during the Cold War." But the tunnels also saw more than their share of clandestine liaisons, according to Ancoran John Force, who "walked in on one too many of those back in the day." Force notes the tunnels have been "locked" since about 1992. Deliberately self-contained, Ancora Psychiatric Hospital had its own laundry, sanitation department, power plant, police and fire departments. Employees shopped at the on-grounds cottage store and placed orders for fresh meat and produce. Summers meant swimming in the hospital pool. There was also a chapel and a cafeteria used by both hospital staff and high-functioning patients. And to the children who grew up in Ancora, seeing institutionalized patients was as common as seeing the school buses that picked them up and dropped them off along Spring Garden Road.

Living with 'crazies'Long before anyone heard of political correctness, it never bothered the Ancorans to be around "the crazies," according to Ann Ziller. That included the patients in the children's unit, where she and Kathy Longo remembered distributing

|

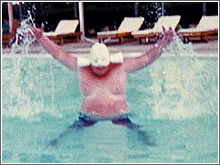

| Bob Blazer, whose family moved into Edgewood in 1957 when the horror movie classic 'Creature From The Black Lagoon' was popular, submitted this photo from the Ancora swimming pool. He would only identify the subject as 'The Monster of the Chlorine Lagoon.' Larger |

Easter candy, having summer barbecues, and bobbing for apples at Halloween parties.

As described by Lisa Morgan Carney, "the patients were actually our neighbors in many ways. We swam; played and watched little league games; played tennis and basketball; explored; rode our bikes and hung out in general, often on the hospital grounds. We got to know different patients who were often seen walking the grounds."

Just like kids today hang out at the mall and people-watch, the 'Ancora kids' hung out at a little luncheonette behind the main hospital building and observed the patients. Patients like an older black man they called 'My Man' because, as Lee Guldin explained, "he would always address [fellow Ancoran] Neil Cuomo as 'my man'." Then there was a patient named Rosie who would come to their table and ask, "Gotta dime?" After Guldin and his friends said no, she would stand there for a second, thinking, then ask, "Gotta nickel?" Guldin summed it up, "Funny place, that Ancora."

Patient encounters commonplace

To the young Ancorans, patient encounters were so commonplace Dave Helfand only recalls one time life on the grounds of a psychiatric hospital seemed unusual to him. "I remember one time talking to my friend from outside his bedroom window. A man -- obviously an escaped patient -- ran by and told me not to tell anyone where he went before heading off into the woods. A couple seconds later some police and others came looking for him. Naturally, I told them which way he went."

Patient escapes, or elopements as they were euphemistically called, were simply

|

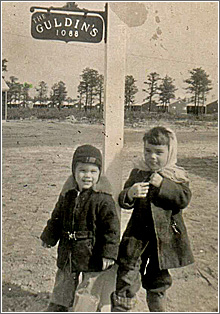

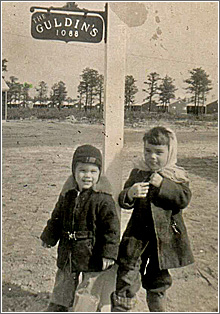

| Lee Guldin and Cindy Jennings Wheeler outside the Guldin home in Edgewood. Guldin remembers drug-fogged patients wandering off the grounds and getting lost. Larger |

part of growing up in Ancora and, to quote Denise Guldin Devecchio, "No big deal." Nonviolent patients were often permitted to wander at will. Some wandered off grounds and got lost; others, on regimens of early antipsychotic drugs like Stelazine or Thorazine, "didn't know where they were in the first place," according to Lee Guldin. As Ancoran Jacque Wooton-Carver explained, patients permitted to walk the grounds were on "elopement precautions" -- meaning staff was supposed to keep them in sight and record their whereabouts. "Patients considered capable of running away were mainly kept in locked wards. At mealtimes, those patients were taken to the cafeteria through the hospital's underground tunnels rather than across the open grounds where they might pose an escape risk."

High-risk walk-aways

For patients who did wander off, freedom was fleeting. Hospital security, grounds crews and maintenance personnel made routine drive-through rounds of the property. Later, as Ancoran John Force remembers, a program in the late 1980s through mid-'90s used nearby Leesburg prison inmates, accompanied by physician staff, Ancora police and fire departments, to conduct well-organized, thorough grid searches of the wooded perimeter for high-risk walk-aways Force described as "usually geriatric or suicidal patients."

Anyone who was "out of bounds" was picked up and taken back to the hospital. And children growing up in Ancora knew exactly what to do if they ran into a patient walking off grounds. Lee Guldin recalled, "We were to report them as soon as we could, describe what they looked like, and where

|

| Young Ann Ziller on the front step of her home. Her parents warned her to never confront any of the patients who wandered into the Edgewood community. Larger |

they were headed." As for Lisa Morgan Carney, she still remembers "561-1700 -- Hello, Security!" Just as the young Ancorans knew what TO do, they also knew what NOT to do. While Ann Ziller was never afraid of the patients, she clearly remembered "my parents telling us not to confront them." Jimmy Owens' mother worked as a police officer at the hospital. Though he was never afraid of the patients, "there were some bad ones, and our parents in some way made sure we all knew which ones they were." Bob Blazer, whose family moved into the Edgewood Homes in 1957, summed it up by saying, "While I didn't fear them, I didn't trust them either."

Suicide on the railroad tracks

Most elopements ended quietly, with patients found and returned to the safety of the wards. But Jacque Wooton Carver recalled "rare occurrences that ended up badly." One such occurrence resulted in the suicide of a patient who left the hospital grounds, found the nearby railroad tracks and lay across them, waiting for the train. At the time, Lee Guldin's father was the hospital's Identification Officer, charged with fingerprinting and photographing patients institutionalized at Ancora. Guldin remembers his dad being called to the scene. "I remember hearing his conversation with Dave Longo about the gruesome details he had to photograph. That was very sad." To this day, Guldin can tell you exactly where the suicide occurred: "Near the water tower behind the pool, close to what we called the Hidden Lakes."

But for the most part, Ancorans remember their growing up as a time of fun. There was always something to do -- and plenty of friends to do it with. There

|

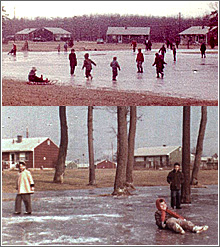

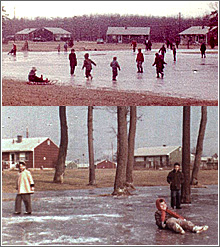

| A flooded field in front of the Edgewood homes made a perfect shallow ice skating venue. Larger |

were forts to build in the woods and frogs to catch in the swamps; a nearby lake and pick-your-own fields of strawberries and blueberries in Hammonton; and great adventures to be had along the railroad tracks. Kids being kids, the young Ancorans made their own fun, no matter what the season. Winter meant sledding and ice skating. Ann Ziller remembers, "our dads tied sleds in a chain to the bumper of a car and pulled us all around the 100 homes." For the more adventurous, hospital grounds crews blocked off a section of road below the water tower hill where, as Bob Blazer recalled, "they pulled a flatbed with a tractor uphill as far as we wanted, then we'd get off with our Flexible Flyers and down that hill we'd go!" And when the fire chief clogged the drain in the middle of the open field and flooded it with water, there was good ice skating right in their own backyards.

Santa on a fire truck

When it came to Christmas at Ancora, Mike Scardino will never forget carols coming from the main building with its Christmas tree atop the roof; tin soldiers and a Nativity scene outside the chapel; and the staff houses all decorated for the season. And every 'Ancora kid' remembers the annual tradition of Santa on the hospital fire truck. Kathy Longo chuckles at the memory of Santa and the firemen "keeping warm by drinking hot toddies" as they made their rounds on those cold winter nights.

The first warm day of spring brought four or five kids pushing their dads' lawnmowers to the big field in

|

| The Ancora kids' baseball team. Larger |

the little village to cut out a baseball diamond. There were plenty of wide-open spaces to ride bikes. Then there was the year most Ancorans got outdoor metal roller skates -- the ones that clipped to your shoes and adjusted with keys you hung around your neck. Lisa Morgan Carney remembers how "we'd all skate around and around the block -- you could hear us coming from a mile away." Patients and children in the pool

Summers meant swimming in the hospital pool. Open every day at 4:30 PM and on Saturdays from 1-5 PM, it was where every Ancoran went and most learned to swim. It was also the place for pool shows put on by the patients, employees and their children. Lee Guldin remembers one patient who "would do all kinds of crazy dives and go the entire length of the pool holding his breath for what seemed to me, back then, to be at least 20 minutes!"

As a kid, Bob Blazer looked forward to the firemen's picnics every summer. For about $2 a head, there were hot dogs, clams, corn on the cob, cold watermelon, coffee, beer and birch beer on tap -- "plus, more of our moms' desserts than you could shake a pie fork at." And Ancorans who grew up in the late '50s - early '60s did what most other South Jersey kids did every summer -- they chased the mosquito-fogging truck on their bikes through the neighborhood as it pumped out its thick white clouds of DDT.

As summer turned to fall, Mike Scardino remembered "football games with kids who didn't speak English," while Jimmy Owens looked forward to

|

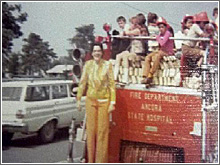

| Block parties that included rides on Ancora fire trucks were a popular summer and fall event. Larger |

"playing street hockey with homemade goalie pads from seat-cushion foam and shoe laces." Friday night dances were given by the Ladies Auxiliary in the community center; and movies like the Beatles' 'Help!' and the 1957 tear jerker 'Old Yeller,' starring Fess Parker and young actor/Mouseketeer Tommy Kirk, were screened in the recreation hall. Looking back, Dave Helfand considers the best part of growing up in Ancora as "the friends." In the 100-homes community, "it always felt like there was an endless supply of friends to visit at any time." But when it came to friends from outside the community, Bob Blazer recalls how "it seemed all roads were one-way. I could visit at any time, but my friends rarely got permission from their folks to visit Ancora -- geez, it could give a guy a complex."

Ancoran mischief

The Ancorans were also pretty good at making mischief and getting into trouble. Jimmy 'Butchy' Owens remembers how he and a friend "would find outdated magazines and sell them to the Filipino lady who lived across from the Kellys. One day her husband was home. He invited us in. Next thing I remember was him picking up a big pole lamp and chasing us out of the house. We never tried that again."

Ann Ziller remembered alcohol being one of their biggest temptations as teenagers. "My dad always had a half-gallon of whiskey in our china closet. One day Phil Panarella, Keith 'Skip' Wooton and I stole the whiskey and

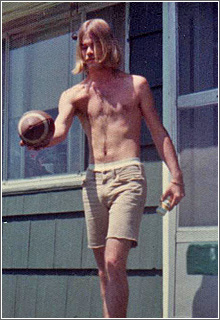

|

| Teenage football player Lee Guldin also remembers himself as something of a firebug who set the surrounding woods ablaze. His father, at the time, was Ancora fire chief.

Larger |

went into the nearby sweet potato field and got plastered. Can't stand the taste of whiskey to this day." Other Ancorans paid a price for playing with matches out in the grassy fields and woods surrounding the Edgewood Homes. Beth McClintock-Storey started a fire behind the shed in her yard when she was about 10 years old so she and her brother could toast marshmallows. "Got my ass beat and was grounded for what seemed like forever for that one." But Lee Guldin seems to have had a special talent for setting the woods on fire. The first time he didn't get caught; but another time, when he and a friend lit the woods on fire, the entire neighborhood was engulfed with smoke. "That time we did get caught and I paid dearly. Oh, by the way, did I mention my dad was Fire Chief at the time?"

Officer Markowski

Hands down, one of the kids' favorite targets when it came to mischief and mayhem was an Ancora police officer named Stanley Markowski. They remember waiting for those nights when he was on duty, watching for his police car and playing havoc on poor Stan in every way imaginable. Bob Blazer chuckles as he recounts one "Stan" memory. He and a buddy had a set of walkie-talkies that picked up and transmitted messages over the Ancora police channel. As usual, they waited for Stan to be on duty. "From our positions in the big field, we used the most official voices two 15-year-old boys could muster to send him racing from one end of Edgewood to the other. Stan being Stan, it took him a while to catch on and stop responding to us. We eventually gave up and went back to my house to get a drink."

Then there was Mischief Night. Like most other kids, the Ancorans toilet-papered the neighborhood, soaped windows,

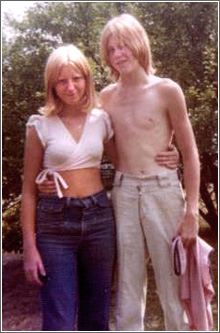

|

| Teen Ancorans Barbara George and Jimmy 'Butchy' Owens. Owens recalls a Mischief Night prank involing a possum. Larger |

left burning bags of doggie droppings on doorsteps, threw eggs and put sugar in gas tanks. But Jimmy 'Butchy' Owens recalled one Mischief Night when he and a friend played a prank on the couple living in the Owens' old house on Twig Lane. "We put a possum up on the outside light looking down at the front door. We knocked on the door and ran across the street into the field. The man opened the door and it took him a minute or so, but when he looked up and saw that possum looking at him, we almost died laughing." Multicultural neighborhood

As adults, the Ancorans looked back on the pros and cons of growing up in a community that was a melting pot of so many cultures, races and ethnicities. The families who lived in the Edgewood homes were white, African-American, Latino, Indian, Filipino, Asian, Slavic, Turkish, Greek, Italian and Spanish; they were single families, blended families, blue-collar and white-collar families. And the customs and traditions each family brought with it helped influence the tastes -- and fuel the rumor mill -- of the tight-knit, little 100-home neighborhood.

Bob Blazer recalled how his neighbors shared Korean foods with his family. "My favorites were the thinly-sliced, marinated and grilled beef and beef short ribs. That meat fell right off the bones." Blazer goes on to recall a dish he remembers looked like ferns. "Mrs. Yoo asked me what I knew about them, and I told her the woods were full of them. She said, 'Show me,' and I did -- you'd have thought I showed her a gold mine."

Deborah Rossetti Daniels remembered each house having a different smell because of the ethnic food each family cooked, and "ate yogurt for the first time in the home of a Greek family."

There was the story of an Indian couple whose house was overrun with roaches because,

|

| Aside from the close communal cooperation required to maintain an isolated 100-home village, former residents remember the unusual level of racial diversity -- and harmony -- throughout Edgewood and the hospital's staff. Larger |

as they explained, it was against their beliefs to kill anything. Then there were those rumors about a Filipino family who always had puppies, but never any adult dogs other than the breeder. After they moved and piles of what looked like puppy bones were found in their backyard, more than one Ancoran was convinced they had been breeding puppies as food which, according to Barbara George, "may have been OK in their culture, but we were all quite upset about it." As Ancoran Jacque Wooton-Carver explained, "It was interesting to grow up there in the 1960s. I never could understand the racial stuff, because I felt like Ancora was its own league of nations. Every color of man lived there, and we grew up learning about the differences in people, but that people were people after all."

Prison workers

Ancora was also home to a prison unit from what was then Leesburg State Prison, now known as Southern State Correctional Facility in Delmont, Maurice Township, NJ. In 1955 an average of 30 inmates lived there at Ancora. They helped clear the land for the hospital, grade and seed the grounds, and provided the physical labor required to clean buildings and move furniture as the new Ancora Psychiatric Hospital prepared to open its doors in April of that year.

When Ann Ziller was growing up in the 1960s, the inmates were only housed in one building. "They had to

|

| Fireman and Ancora heavy equipment operator Jimmy Lynch didn't want his wife and daughter around when prison laborers were working on the grounds. Larger |

be exemplary inmates to get the Ancora job, since it was considered a privilege." But Ziller recalled some of them working with her father, Jimmy Lynch, who was the heavy equipment operator for the whole hospital, noting, "he would never let my mother or me come around when they were working with him." In the late 1970s Leesburg sent several dozen low-risk inmates to Ancora to alleviate overcrowding. John Force lived at Edgewood for four years but worked at the hospital for 23 years; he explained how prisoners were assigned various tasks at the hospital -- for example, trash detail and working in the laundry. "By then, all inmates were housed in two buildings -- Spruce and Willow (the former adolescent unit) with an average population of around 150. There were instances where prisoners escaped and one incident of an inmate raping a nurse. At one point, hospital pool privileges were granted to inmates, but that didn't last long. They played softball on grounds, but were confined to the area of Spruce Hall. And they were granted one or two nights a week in the hospital gym for basketball or volleyball. Always escorted by corrections officers, any violations of the rules resulted in a return to the main prison for the remainder of the inmate's sentence."

Arresting the ball players

Bob Blazer remembers the Leesburg Unit softball team in the '70s and '80s, when he was involved with the local softball league. "Their talent was so-so, but boy did they behave! They played 'away' games -- at first at all the fields, but, later, weren't permitted to play on Winslow Township-run fields. No incidents ever occurred involving the Leesburg team. But, at the time, the Winslow Police Department was headed by a captain who didn't like the idea of prisoners in his town." Blazer continues, "At one point he had a whole contingent of officers in riot gear arrest two Corrections Officers, the hospital Recreation Officer for aiding, and the softball team for armed escape. Armed? Of course -- with bats and balls. It was after this the Leesburg team played only home games." As it turned out, the Leesburg Unit softball team lasted longer than that police captain.

The dozens of Ancorans who grew up in the unique little 100-home community over its nearly 45-year existence and gathered for their first reunion at Our Lady of Mount Carmel

|

| An aerial view of the Edgewood homes site shows the outlines of the tract's three former streets which are now dirt ruts. All other evidence of the village's existence is gone. Larger |

Society that hot August afternoon had one more thing in common. For them, there was no going home again. By 2004, demolition of the Edgewood Homes was well underway. Outside contractors were hired by the State to come in and remove asbestos before tearing down the houses. Ancoran John Force was on duty with the fire department the day the last home was slated to come down. "A couple guys overseeing the project knew I lived in the development. They called and requested I respond to their location. When I arrived, they asked me to do the honor of taking down the last house. So I had the 'privilege' of taking that last Edgewood Home down with a backhoe. I will tell you, it was bittersweet at best."

An 'erased' community

Today, all vestiges of what was once a thriving physical community are gone; even the streets, sewers and concrete slabs on which the vanished homes once stood were ripped up and removed. An arc of double dirt ruts -- the former Park Drive -- traverses what is now an area thick with trees and dense underbrush.

Ask Ancorans how they feel about all traces of their childhood homes being swept away, and their sense of sadness and disbelief is almost palpable. Social Worker Dave Helfand drove by his old house on the way to work every day.

|

| During demolition, Lisa Morgan Carney and her sister, Leslie Morgan, returned to their former Edgewood home to gather physical momentos of their childhood. Larger |

"As they began to knock down the homes, I remember telling colleagues it was sad -- I was almost counting down the days until they got to my home. That was a very sad day for me. I remember thinking I should ask the demolition crews if I could visit just one last time to take photos. I never did -- and in hindsight I wish I had." But some 'Ancora kids' were able to go back one last time. Lisa Morgan Carney's mother was ill when the State began to let the houses go; they weren't torn down all at once. She remembers how she and her sister, Leslie Morgan, "went back before my mom's funeral in 2002. "We pulled up some of the tiles our dad had put down, dug up the daffodils our mom loved, and picked up some stones from the driveway. All that went with my mom -- by then our house was already gone."

Sad bike ride

Lee Guldin rode his bike through Edgewood when only the foundations were left. Just as Kathy Longo remembers who lived where by the colors of the houses, Guldin would "identify the foundations -- the Blazers' home, then Rossettis, Cuomos, Zanella and so on" on those rides.

Ann Ziller described feeling "broken-hearted that it's all gone. I know it was a time-and-place thing but it just broke my heart to see it last year when I came

|

| Deborah Rossetti Daniels felt 'erased' when she recently drove by where her Edgewood home once stood. Larger |

back. It's like we were simply erased." That feeling of being "erased" was echoed by Deborah Rossetti Daniels. She and her sister drove past the sign for Spring Garden Road about five years ago, unaware that the little village of 100 homes had been torn down. While she expected to see falling-down houses and overgrown yards, she describes complete shock at what she did see.

"There was nothing there! It was like being in the Twilight Zone -- like living there had never happened. Sort of creepy and disturbing, the feeling stuck with me for a long time. Did all our families really live and grow up there? Was the community demolished because it was a bad place? It was just wiped off the face of the earth and left to return to its natural state. But, oh, if those pines could talk."

Sandy Levins is the President of the Camden County Historical Society and proprietor of HistoricFauxFoods.com, a company that makes historically accurate fake foods for historic homes and museums. |